The Principality of Lippe, Germany

The ancestral area of the Junkermeiers is the Principality of Lippe in Germany.

Contents |

The archives of Lippe

The official records of Lippe are extraordinary in the completeness of their preservation. None of the archive materials have been lost, nor have they ever been moved or dispersed, as happened to part of the archives of Lippe's neighbors. Very early, the rulers recognized that all people who were not actually paupers were worth taxing, and they thus had to be kept track of by means of censuses and tax and rent lists.

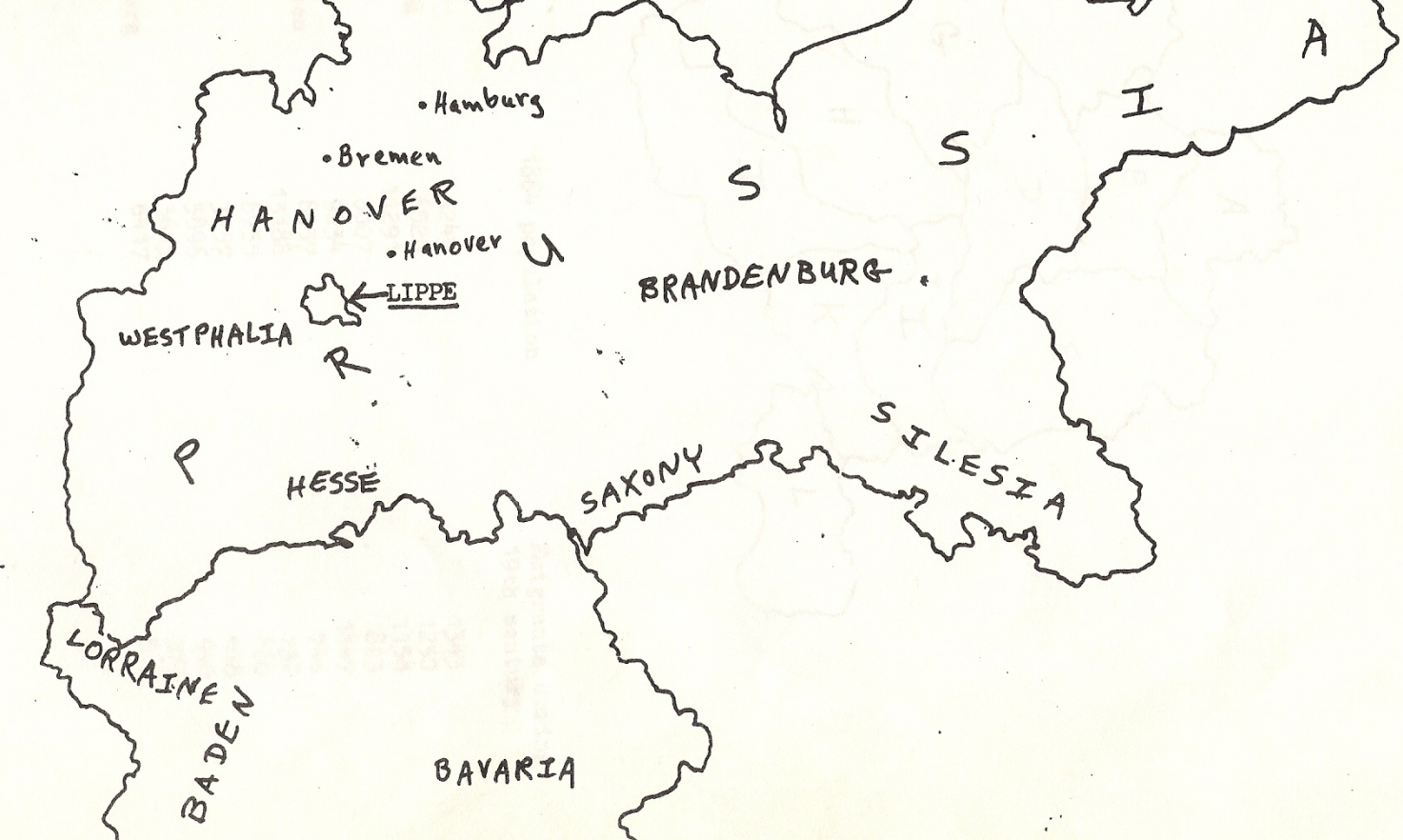

Geography

Lippe comprised approximately 1200 square kilometers. A thirty-mile journey, or a day's steady riding by horse, would take the traveller across the entire principality. Over the centuries it was characterized by the longevity of its dynasty, its secure, isolated geographical position, and its economic backwardness. Since 1946/47, Lippe forms the northeastern corner of the present state of Nordrhein-Westfalen, which today is one of the richest and largest states of the Federal Republic of Germany.

History

Before 1800

The principality of Lippe was established by Bernard I (1113-1144) under a grant from the Emperor Lothiar. Bernard assumed the title of Noble Lord of Lippe (edler Herr von Lippe), and his descendants were known as Counts. The area was self-governing from 1168 until the end of World War I in 1918. Until 1638, the area was under a single ruler, with the ruling family located at Detmold. Following Simon VI, who died in 1613, three other branches of the family developed, all descended from him, and the Counts of Lippe-Biesterfeld, and Lippe-Weisenfeld and the Princes of Schaumberg-Lippe ruled parts of the original area, with the main line at Detmold continuing. Although the official name of the area continued to be Lippe, the splitting up of the territory left a possible confusion as to which Lippe was meant, so that conversationally the area of the ruling family at Detmold became known as Lippe-Detmold. The Junkermeiers in America always have used this popular name of Lippe-Detmold to refer to their native area.

Religion

The religion of Lippe was, of course, Roman Catholicism until the Reformation. Unofficially, Lippe became Lutheran in 1538. In 1571 an official decree was made to recognize the Lutheran (Evangelical) victory over Catholicism in Lippe. Under the rule of Simon VI in 1605, Lippe went Calvinist (Reformed). Eventually the term Evangelical Reformed came to describe the predominant church in Lippe.

The state maintained strict control over religion in Lippe. In December, 1689, two Stemmen men, Alheit Peters and Schmidt Grethe, were tortured into confession and executed for Zauberei (magic). This was part of an official campaign to eradicate deviations from the state church. The fervent, personal, conversion-type religion, which swept through American society with the "Great Awakening", was not permitted in Germany, where it was seen as a threat to the state's authority. German immigrants rejoiced in the freedom to respond whole-heartedly to the warm, personal religious experience in the new country, America.

Division of labor

Tax lists date from 1609, and the first census, showing a population of 50,000, was made in 1776. A more accurate census was made in 1788, revealing the following composition of the population: 8 percent establishment (court, nobles, officials, clergy, army, estate managers), 17 percent town dwellers, and 75 percent rural dwellers (peasant farmers, serfs, servants, farm laborers).

After 1800

In the 50 years between 1830-1880, the population of Lippe increased by 25 percent. Agriculture still was the principal occupation, but migrant work was increasing steadily. Northern Lippe, the locality of the Junkermeiers, had the principality's greatest number of very small, widely-scattered plots of privately-owned farm land, as well as the greatest number of large farm estates. The poor farmer who owned his own little piece of land found it too small to furnish a living, but he could not add to his holdings because of the large estates. For centuries, hand-weaving of linen and spinning were an important source of income for the poor farmers and farm labors in eking out their living. But after 1830, there was a rapid decline in weaving and spinning, because of the introduction of mechanical weaving, the increasing use of cotton, and an embargo against German linen in some countries. Hard hit by this loss of supplemental income, the poor families saw no recourse except migrant work as brick makers or emigration. Between 1833-1855, the number of migrant brick makers in Lippe increased from 938 to 7361. In the ten years following 1870, 4933 people emigrated from Lippe, of which 1364 went overseas. From 1840-1880, 71 percent of the emigrants from Lippe were farmers or farm workers.Brick-making

In order to acquaint the American Junkermeier descendants with the migrant brick-making work to which many men of Lippe turned in order to support their families, the following quotation is offered from the author Theodore Fontane, in which he describes his visit to a brick factory at Glindow, near Brandenburg, in 1870, where the 500 workers in the factory included migrants from Lippe:

| “ | Those from Lippe, men only, come in April and stay until the middle of October. They stay in a large house of three stories: kitchen, dining room and dormitory. They make certain demands: each must have a hand towel for his use. At their head is a boss, who only gives directions and is their manager. He signs the contract, receives the money and divides it. It is piece-work. The materials are supplied, fuel and clay are brought, and the ovens are for their use. All the rest is up to them. At the end of their season, they get 1 2/3 to 2 Taler (1 Taler = 3 Marks) per 1000 bricks. The total for 8 to 10 million bricks is usually no more than 15,000 Taler. But this amount is the result of hard work. The people are exceptionally industrious. They work from 3:00 AM until 8:00 or 9:00 PM; not counting an hour for eating, they work a 17-hour day. They eat in the Lippe way: you could say they live on peas and bacon, both of which are brought in from Lippe by their manager, where they are cheaper and better. In mid-October they return home, each man with about 100 Taler. | ” |

Further evidence that seasonal workers from Lippe were considered exceptionally hard-working and productive is found in pastors’ reports from the 1840s on through the second half of that century. Here is a short quotation from one of those reports:

| “ | Workers from Lippe are, at least where hand labor is involved, the equal of all others in Germany, and excel those from other countries in industriousness and endurance. Therefore they were welcome where those qualities, especially healthiness and physical strength, are the prime factors. | ” |

The lives of the Junkermeiers who immigrated to America in the 19th century are proof of the truth of these quoted descriptions of the workers of Lippe.

Gallery

Germany in 1871, showing the location of Lippe: